Tramping down cold limestone steps into a church crypt after midnight might once have scared the bejammers out of me. But I paid little heed to the blue flame lights, strange ornate wood coffins, and mummified remains as I descended. I was already sick, sorry, and worn out of ghosts, night bumps, and every blasted form of paranormal activity. All I wanted was one night of uninterrupted sleep in my own home. That wasn’t too much to ask?

The most irritating thing about my sister Annette is that she haunted me when she was alive and then she kept on at it afterwards. I’m sorry Nettie’s dead but she was one of those people not exactly built for old age. She ate too much, smoked too much, and most especially drank too much. So when she fell down the stairs one night three hundred sheets to the wind, and cracked her skull, it wasn’t completely unexpected.

The Mooch, that lousy useless dirt-bird of a boyfriend of hers, he never even had the decency to wake up as she crashed gracelessly down to the tiled floor below. I told him he had a week to move out as we sat post-funeral in the Spa Hotel chomping on egg sandwiches and draining pint bottles of Magners.

“Where’m I supposed to go?” he says to me, his bleary eyes pleading. It was the same hangdog eyes he used to shake down my sister if there was only a single cigarette left in the pack after the shops were closed.

“Fooked if I know,” I replied. “But I’ll tell you what – I’ll help you pack your things.”

Meself and Annette had a complicated relationship. I can admit now I loved her but I never would’ve told her that. She was a cranky old sort, like a dying wasp in the autumn. And the drink did nothing to soften her. Still, we managed to live together under one roof all our lives without killing each other, even after our parents passed. Though I suppose there never was much choice given neither of us had much of a predisposition for brains or working.

The Mooch though, he was in an altogether different class. I never met a man who put so much effort into avoiding doing anything resembling labour. He was lazy, dirty, rank with BO, and stingy to boot.

Marty, as Annette called him, was the type of guy who’d eat off a filthy plate sooner than wash one. You could find cigarette butts or empty cans of cider anywhere – stubbed out in a plant pot or crunched up in the coal scuttle. And the way he’d leave the toilet, my christ; even now thinking about it, I get ghastly echoes in my nostrils. I could, and have, filled hours recounting his flaws so that my buddies down in the Glimmer Man got bored listening to me.

Watching the Mooch plod down the driveway with his sweaty rags in two old gear-bags that Sunday afternoon, I was as happy as a dog rolling in fox dirt. “The very best of good luck to you,” I shouted at him as he turned one final time, wondering if I would have a last-minute change of heart. Two fooking chances.

I was sprawled on the couch later on, smoking a pack of Carroll’s and sipping my way through a six-pack of Karpackie. Happy happy. Every half hour or so, I’d let out a contented ‘ahhhh’, as if to remind myself the Mooch was gone and no longer able to cadge my beer or cigarettes, or stink the place out with his flatulence. There was horse racing on Sky Sports from Aqueduct and Finger Lakes, and I was throwing a fiver on here and there and coming out a little bit ahead.

It was very unusual for me to fall asleep on the well-stained settee. I was more used to the other two clattering about in the loo, stomping up the stairs, or sniping at one another. And it wasn’t a light sleep either because when the quarter-full Powers whiskey bottle smashed into smithereens on the wood floor, I wasn’t fully sure where I was. I didn’t even think to put my slippers back on and a little shard of glass cut into the fleshy part of the sole of my foot as I went to examine the mess.

“Dirty fooker,” I roared as the sharp pain and bracing smell of liquor brought me back to my full senses. The door of the drinks cabinet was wide open and that was peculiar because I was sure I hadn’t gone near it. I started second-guessing my memory, that perhaps I had blacked out a portion of the evening, wouldn’t have been the first time. But then I noticed there was still a full can of Karpackie in the portable cooler and there was no way I would have gone for the spirits as long as there was still some beer left. ‘I’ll clean that in the morning,’ I mumbled to myself as I went off to the bathroom to clean my foot and find a sticking plaster.

My head was pounding when I woke the next morning. Between that and the sorry trail of blood I’d dripped along the floor, up the stairs, and into my room, I decided to call in sick. “I’m after injuring me foot,” I told the manager at the waste department of the city council where I worked, a bit.

“Ah, for christ’s sake,” he said. “Aren’t you just after a warning about the amount of illness leave you’ve been taking?”

“Do you want a picture?”

“You better be here tomorrow,” he replied, but I barely heard the word ‘tomorrow’ as I was already hanging up the call.

By the afternoon, I was half-wondering if I should have just gone in, and sat about for the day saying I was incapacitated. There’d been whispers the council had hired private detectives to crack down on chronic absentees like myself. So that left me confined to my quarters for the day. It was a crap job but I didn’t want to lose it; it paid pretty well, a sight better than what I would’ve got on the dole.

In the evening, I got itchy feet and decided I’d chance a trip in to Stoneybatter to see if any of my compadres was enjoying a Monday night drink. One pint became two, then four, and it was well after midnight by the time I was cruising along the Chapelizod Road in a taxi on the way back home.

My mind was already fixed on that last remaining can of Karpackie in the fridge thinking of it fizzing down nice and slow in a blissful solitary silence. The cab driver told me the fare was €14.50 so I gave him fifteen and said to keep the change.

There was still a little warmth in the night air when I stepped out of the car. We were halfway through one of those Dublin Septembers that made the city just about tolerable after another sodden summer. So when I opened the front door and I could suddenly see my breath on the air in the hallway, it was like stepping inside-out, and not outside-in. Stranger again was the lit cigarette that sat in an ashtray on the living room table. The smoke seemed to hover and you could see the ember of tobacco burning like somebody was taking a drag from it. My first thought was whether there might be a burglar but when I checked all the doors and windows, there was no sign of any intruder. When I extinguished the cigarette, I could see a smear of bright pink lipstick on the filter. That can of beer I’d been so looking forward to went down very uneasily indeed.

In the weeks that followed, my house became a corny house of horrors. There was inexplicable movement of objects and furniture, flashing shadows and creaking of every tone and timbre. At night, I would often hear a nagging whine, like my tormentor had caught me putting empty sweet wrappers back into a box of chocolates. It was impossible to get comfortable in bed because if the spectral activity began, the temperature would drop precipitously. Yet when I left the radiator on just in case, I’d awake clammy and in a hot fugue.

I was a little frightened at the start of course. Who wouldn’t be? But as it became apparent my incorporeal interloper intended no harm, it was far more maddening than malevolent. The nightly intercessions continued so that my eyes went baggy and my punctuality at work, never noteworthy, became even worse. The final straw was when I came home from a sing-song in Delaney’s and found the word ‘Marty’ scrawled in some kind of foul brown goo on the wall of my bedroom.

The only time you’d catch me in church was for weddings and funerals, but the priest still knew me because my parents were devout. On a pew in the front row of the Church of the Nativity, Father Doherty asked me what he could do for me. I think he was expecting some long lament about how hard things had been since Annette died.

“I think my sister is haunting me,” I said.

He did that priestly thing of pausing a few seconds before saying anything, like he had to do a quick check-in with god.

“Many times, people experience strange things after the loss of somebody very close to them. It’s just our mind trying to come to terms with the loss.”

We went round and round in circles, like two dogs sniffing each other’s backsides. Him trying to convince me it was some profound manifestation of grief and how I should consider counselling; me explaining that I’d hardly smeared god knows what on the wall of my own house without realising it.

The tiredness had made me a little crabby and after fifteen minutes of the two of us talking, our words whistling past each other like bullets fired by panicky soldiers, my patience finally gave way.

“A lot of fooking good any of that sh**e is to me,” I said.

“Brendan,” he said, “this is a house of god and we don’t speak like that here.”

“I’m sorry Father,” I said, “I haven’t had a solid night of sleep in weeks.”

“That’s OK,” he replied. “If you’re serious about this though. There’s a priest, ex-priest really, who I trained with in the seminary in Maynooth. Specialises in – how should I say? Possession, apparitions, the inexplicable. I’ll send his number to you on WhatsApp.”

Father, or The Ex-Father, Crowley had a top-floor office above a furniture store on Capel Street. On the way upstairs, trying not to trip over thread-worn carpet, I passed a watch repair shop, a dubious-looking massage parlour, and an even more dubious-looking company registration service. There was a sign outside his room that said ‘Divination’. The office was little bigger than a cubby, with leaning towers of archive boxes and musty piles of yellowing newspapers. It was the sort of place that would give a fire safety inspector a rotten dose of heartburn.

“Brendan, is it?” he said, pushing an almost-finished tinfoil container of fried rice to the edge of his desk. There were a couple of grains still lodged in his unkempt grey-black beard.

“Are you a man who takes an afternoon drink?” he asked. “I like my clients to feel comfortable.”

“I’ve been known to,” he said.

He whipped out a bottle of Jameson from a locker along with two small glasses that didn’t look to have troubled a sink in the recent past.

“Now, son” he said, “tell me all of your troubles.”

As I spoke, he was picking his nose and every so often, he’d dislodge something. He’d have a good look at the goo on the top of his index finger and then gobble it down as if he’d found a truffle underneath a hazel tree. “Yes, yes,” he’d say occasionally, his head nodding vigorously.

When at last I’d told him about how the Mooch’s name had been daubed on the wall, he gave his beard a stroke and the rice grains came loose and fell on the desk.

“An absolutely classic case,” he said.

“How’d we get rid of her?” I asked.

“An exorcism of course,” he said as if I had just asked one of the most foolish questions ever uttered.

“Well, if that’s what’s required, that’s what required.”

“I do need to warn you though,” he said. “An exorcism will generally sent the exorcised straight to hell.”

I began stroking my own beard then. I mean my sister had been an awful scourge; no one would ever have called her a model citizen. It was harder to think of the sins she hadn’t committed. But an infinity of suffering? A couple of weeks might soften her cough a little – but not an eternity.

“And would hell be just as bad as you’d expect?” I asked.

“Oh yeah,” said Crowley. “Worse even.”

“Fook it,” I replied. “I couldn’t do that to her.”

I sipped the last of the whiskey, and sat back in the plastic bucket chair. A crack in it was pinching my upper thigh and it reminded me of being in the principal’s office back in primary school.

“There is an alternative,” the diviner said.

“Oh?”

“You could go to dispute resolution.”

“Dispute resolution?”

“Indeed,” he said. “You sit down with the Spectral Arbitrator and you hammer out some sort of a compromise.”

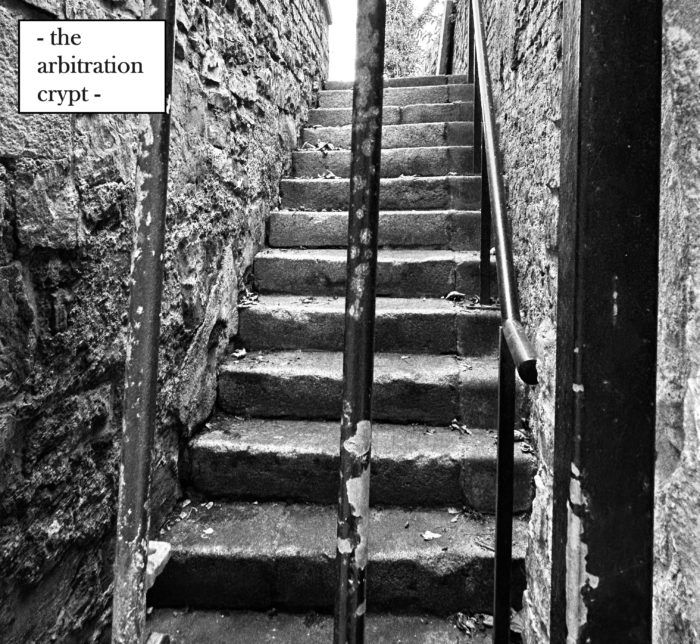

And that? That is how I came to be walking along the cobbles of Bow Street blowing hard on my freezing hands because I’d forgotten my gloves. You’d hardly notice the back entrance to St Michan’s Church unless you were searching for it. A non-descript iron gate led into a steep bank of stone steps that rose up to the old graveyard.

It was flanked on both sides by low-rise office blocks and up ahead, I could see a bluish glow that seemed to be rising from the ground like a gas flare at a rubbish dump. As I approached, I saw two thick rusting metal doors thrown open and leading directly down into the crypt. The Ex-Father Crowley was supposed to have come with me but he’d been called to deal with a belligerent poltergeist up in Cabra that evening. Whatever was beneath the ground here in Smithfield, I’d have to face it alone.

I walked down a long corridor that put me in mind of a Victorian sewer. The limestone of the walls and barrel-vaulted roof was rough like it had been scraped with steel wool. It was this rock they said that kept the air dry and helped preserve the corpses that were interred in the vault.

I passed burial chambers guarded with industrial age gates imprinted with the names of long-dead reverends. Ahead, I could hear a faint bustling, clacking, scraping, and grumbling. I followed the sound until I came to an old oak door riven with woodworm. A sign hung crookedly on it, dangling from a twelve-inch nail – ‘The Arbitration Crypt’, it said.

‘What the fook am I doing here?’ I whispered to myself as I rapped gently on the wood.

The voice that responded had a distinctive squeaky Dublin accent. “Come in, come in, how are tings?” they said. I say they because I could not tell what gender the arbitrator was. One second, they were female, the next male. Hair was long at one glance, shorter in the next. Their face softened and hardened according to the dim light so that you might catch a glimpse of lipstick or mascara that would be gone an instant later. Their smile though was like the embrace of a cold beer on a scorching day, so that I fell into what seemed like a state of ever-so-subtle tranquilisation.

“Your sister’ll be here any second,” the arbitrator said, their voice lolling and lilting.

I just nodded, expecting Annette to come rattling through the door at any moment. Instead, she materialised on the Chesterfield armchair right next to me. She was looking well too, all things considered. A bit paler than when alive but she’d lost weight and her skin looked fresher like she hadn’t been smoking or drinking quite as much.

“Nettie,” I said and I went to tap her just above the knee. We’d never been ones for hugging and a handshake felt too formal. It didn’t matter anyway because my fingers slipped right through the place her thigh should have been and brushed against the soft red leather of the seat.

“I’m not fooking happy with you Brendan,” she said. Diluting words was not her thing and that evidently had not changed post-mortem.

“Nice to see you too,” I said, and I could already feel my blood pressure rising, memories of my torments like stomach reflux.

The arbitrator broke in. “Now, now,” was all they said but it was enough to slow my pulse and make me reconsider the nasty thing I was just about to say.

“We’re here to end this dispute,” they said, “not to make it worse.”

I was given first chance to speak, explained how I had no obligation to the Mooch. It was my house and my house alone, that was not in dispute. I hadn’t liked it when he lived there and as a house-mate, he was irredeemable. Annette spoke next explaining how she’d had no peace since ‘Marty’ was evicted, that he was now living in a Salvation Army shelter in the city. How she was left stuck in cruel purgatory, left to creep around our family home in Chapelizod each night.

“That’s not my fooking fault,” I said.

“You turfed him out,” replied Annette.

The arbitrator interrupted, their voice like the flute of a cobra charmer. “How can we make this work?”

Back and forth it went and each time that one of us began to seethe, our spectral counsellor would intervene with soft words and that enchanting voice.

I looked at my watch in the glimmer, it was already 3am.

“I’ll give him one more chance,” I said.

“That’s all I’m asking,” said Annette.

“And there’s conditions.”

“Now, we’re getting somewhere,” said the arbitrator. “Let’s talk about them conditions, set ‘em down, and make them binding.”

“Well he has to at least attempt to get a job,” I said. “Even a part-time one and that means a small amount of rent.”

“That’d be good for him,” said Annette.

“He has to clean up after himself – I’m not going to be his maid. A shower every day as well.”

“Fine,” said Annette.

I scratched around in my ear, squinched my eyes, thinking of what else was needed.

“He’s not allowed ask me for drink, cigarettes, or a loan,” I said.

“That’s fair,” said Annette.

“And he’s barred from every toilet in the house except the downstairs one.”

“That all seems grand to me,” said Annette and as I turned to look at her, it seemed like she had changed. As if she was not fully there, that she was readying for departure.

“Sounds like we have the makings of a contract,” said the arbitrator.

I nodded my agreement, aching for sleep. Annette nodded too and I could see the tension in her face dissolving. She reached over with her left hand, placed it on mine. I’m almost sure I could feel the tenderest tendril of her touch.

“I do love you Brendan,” she said. “I hope you know that.”

“I love you too Nettie.”

And with those words, she was gone for good.

“Brendan,” said the arbitrator. “Brendan!”

“Sorry,” I said and my voice was choppy in my throat.

“You can head off now. Get yourself a good night’s sleep. Would you be good enough to push over the doors of the crypt on your way out?”