ONE of the most common criticisms politicians have of journalists is that they are obsessed with TD’s expenses and government waste.

Quite aside from the fact that this obsession is in the public interest, there is actually another much more practical aspect to it.

Ireland’s Freedom of Information law is severely limited, containing a raft of exemptions that cover issues like commercial sensitivity, security matters, personal information, deliberative processes … the list is endless (maybe not quite).

There are so many exemptions in fact that government departments and public bodies will, when refusing access to certain records, often frequently list four or five separate reasons why they do not have to disclose them.

One area, where it seemed that there were none, or at least very few, restrictions was in the realm of political expenses, and their release to the public.

Back in 1999, the Information Commissioner (in a case involving Richard Oakley, then of the Sunday Tribune) decided that political expense claims could not be considered “private papers” of TDs and Senators and that the public interest in releasing them outweighed any right to privacy.

Four years later, the original Freedom of Information Act was gutted by the then Finance Minister Charlie McCreevy, which included the introduction of charges for journalists to make requests.

Yet the changes in 2003 made little difference in the area of political expenses, and they remained one of the most easily requested categories of public records.

In 2009, controversy over political expenses claimed its first high-profile casualty when then Ceann Comhairle John O’Donoghue was forced to resign amid a furore over his travel expenses.

Then, two ex-Ministers — Ivor Callely and Ned O’Keeffe — were discovered to have made fraudulent claims for mobile phone expenses and were subsequently convicted of that.

All the time, pressure had been growing for reform of political expenses and a new system for paying TDs and Senators was eventually decided upon.

It actually ended up being much less transparent than what came before.

Henceforth, TDs and Senators would be paid an allowance for travel and accommodation, the level of which is based on how far they live from Leinster House. They do not submit receipts or invoices to cover that.

A second allowance to cover their political day-to-day expenses was also created. This part of their parliamentary standard allowance is, we are often told entirely ‘vouched’, but it’s nowhere near that simple.

By vouched, it actually means a system whereby TDs and Senators could be selected for random audit each year but otherwise, they would never actually hand over the receipts and invoices to the Oireachtas.

This, it was planned, would protect those records from public scrutiny as if they never left the possession of the TD or Senator, they could more easily be designated as “private papers” or personal information.

There was a weakness however, and that was the fact that the unlucky 10% of politicians selected for audit each year did actually have to hand over their receipts and invoices to the accountancy firm Mazars for scrutiny.

And it was access to those records, held by Mazars under a contract from the Oireachtas, which I first sought access to.

As I suspected they would, Leinster House refused my request. I appealed it, lost. And in a final appeal to the Information Commissioner, I lost again.

The Information Commissioner Peter Tyndall effectively overturned the original decision from 1999 on political expenses saying the new Freedom of Information Act of 2014 had introduced a new provision on what constituted the “private papers” of members.

“It is quite broad in nature and affords a more significant protection for private papers of members of the Houses than previously existed,” wrote Mr Tyndall.

I don’t agree and am still trying to get access to those receipts and invoices (this time for a different year), a process which is still ongoing with the assistance of Right to Know.

Separate to that, the battle over what constituted “private papers” opened on a second front when the Oireachtas introduced new standing orders to expand the definition of what could fall under this umbrella.

It was brought before the Dáil on 17 December, which was the final sitting day before Christmas. From start to finish and without debate — it took just seventeen seconds to introduce.

The definition of “private papers” has been dramatically widened and it is not just requests for political expenses that will suffer.

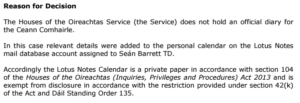

A separate request I made for the diary of the former Ceann Comhairle Sean Barrett has also been refused on the grounds that calendar entries in his email account are “private”.

This is despite the fact that diaries of other officeholders like government ministers — even senior civil servants — are being routinely published by other departments.

The idea of “private papers” has its root in the constitution; where it talks about protecting TDs and Senators from anybody “interfering with, molesting or attempting to corrupt its members in the exercise of their duties”.

This idea had in mind private communications between politicians and their constituents, material relating to official inquiries or committees, perhaps even communications with whistle-blowers … the type of material that needs special protection.

It was never intended simply to keep expenses — or other material — out of the public domain, simply because the release of them might be inconvenient or embarrassing.